A conversation with Monika Vaicenaviciene, Author and Illustrator of WHAT IS A RIVER?

In this interview, Enchanted Lion’s Aubrey Nolan talks with Monika Vaicenavičienė, author and illustrator of What Is A River?, a singular and visually striking picture book that explores the many meanings of a river: as a thread that connects many forms of life, as a meeting place, as a source of magic and mystery. Their conversation follows the winding and flowing path which led Monika to create this book, her artistic practice and materials, and the ‘mapping’ of the book in its early stages, which created its unique narrative structure.

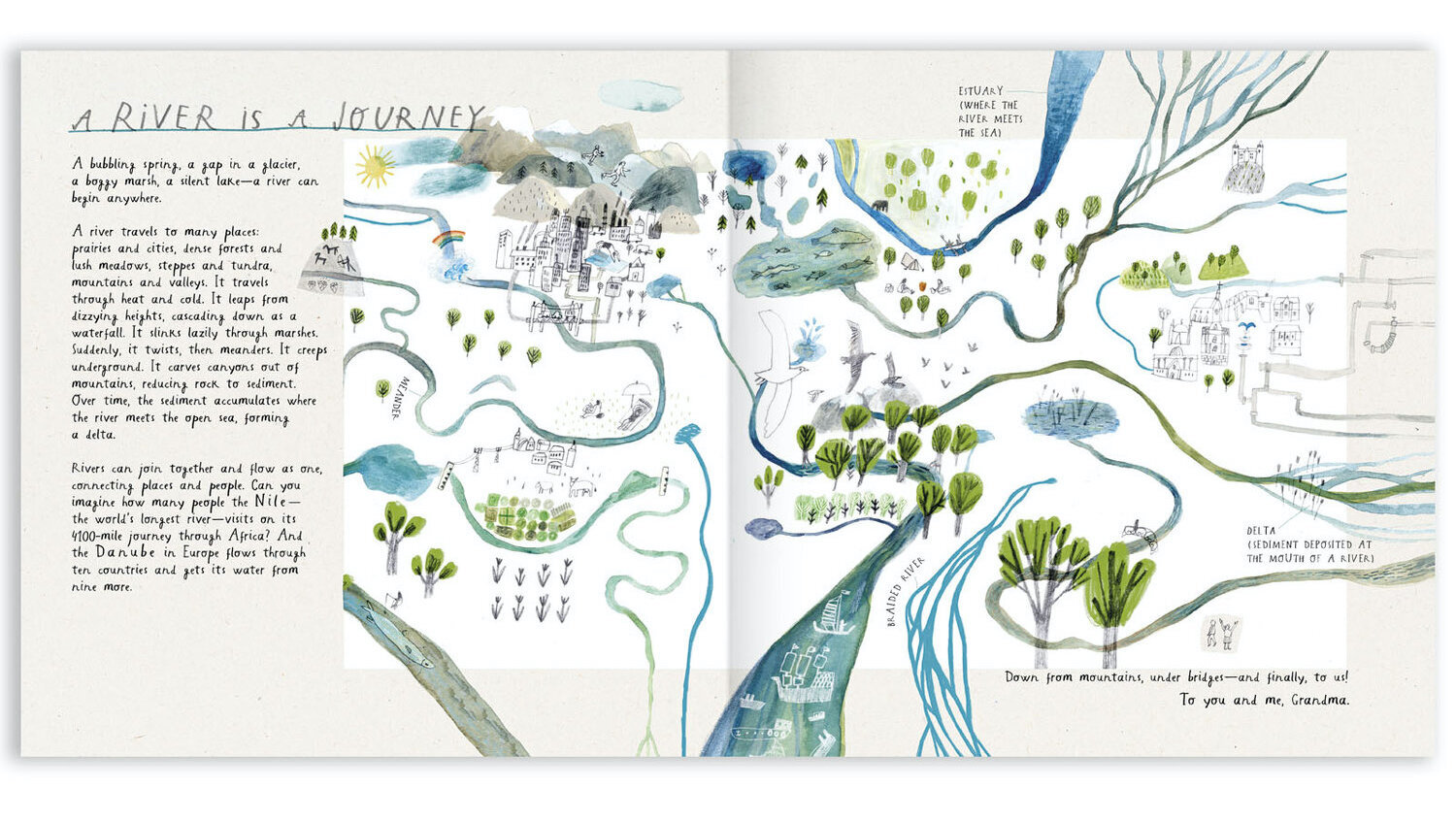

The ‘Journey’ spread from What Is A River?

AN: What Is A River begins with a child asking her grandmother the book’s central question, which sets the journey of the book into motion. What inspired you to create the book within this framework?

MV: It is a long story. I haven’t thought up my book at once; like a river, it had to meander through various turning points and gather quite some sediment and sentiments until it reached me.

I have been interested in geography for a long time. In school, I used to participate in student geography Olympiads; during breaks between lessons, I drew maps of imaginary places with my friends. An interest in the concept of a place as a space where stories from different times and contexts may meet and intersect has followed me ever since.

And as to rivers – I love them. For me, they represent being connected to the world, a sense of neighborhood; being close and far away at the same time; interdependence. This is, of course, quite an abstract and summarized explanation of my relation to them. I lived close to a river throughout my entire childhood. I would go to the riverside with my sister and my grandmothers to play, to read, to have a picnic, to draw, to meet friends, to be alone. These are still vivid and precious memories.

Monika at her hometown river in Lithuania.

Moreover, when I think of rivers, lots of cultural, cartographical, philosophical, linguistic, even typographical associations come to my mind – and offer many starting points for a story to develop: paradise rivers of milk and honey, stream of consciousness, living water of folk tales, flowing current of time … I remember I heard a story once about a Lithuanian deportee to Siberia in the Soviet times who would come to a riverside, sit down and look into the river, hoping that the current would flow her gaze to her beloved left at home. I knew that I wanted to make a book that would carry the gaze of a reader likewise, and would help them to reach faraway places and times by means of imagination.

All of this – and more – I carried with me, and when I got into the Visual Communication Masters program at Konstfack, I decided to make a project dedicated to rivers as part of my thesis. That project turned out to be this book.

An early storyboard for the book.

I decided what kind of book that was going to be: encouraging to explore and ask questions; dealing with beautiful as well as troubled aspects of our relations with rivers, ecological problems, historical sores – a piece of narrative nonfiction. I imagined it was going to be much fun to draw all of the riverscapes, to mix colors for the undulating water – and be a chance to include some maps!

But… how to put together all of the river stories in one entity, how should they flow in my book, how should readers get along? At that time, I was quite interested in traditional folk tales and legends, and their classifications. Perhaps that is why I thought at one point about flying lakes – a common character in Lithuanian folklore: a lake that would hang in the sky until someone guessed its true name. Then they would settle on the Earth. At one point I pondered: but what is that flying lake? Is it the water that is above in the air? Or – that water, but already in a special lake-y form? Are there any fish in it? How about plants? Maybe, similarly, I could just ask: what is a river? Water that flows, a current between riverbanks? An ecosystem? Maybe also a metaphor? A symbol, an archetype?

So that idea set the framework for me, and I began working on a book exploring how a meaning could be expanded in different contexts and how the definition of a river could be layered.

AN: The book is very clear-eyed in its portrayal of human folly and irresponsibility in relation to the natural world, and the subsequent effects that our actions have. What are your hopes for what young readers take away from the book? Do you hope that they put environmentalism into practice more actively?

MV: I would like my book to encourage readers to look with more attention at their surroundings, to look beyond the surface. I think that to care for something, you have to love it, to feel a connection to it, and to do that, you have to know it in its entirety. I hope that my book will help readers to form a relationship with the nature around us, to befriend it.

And I hope that my book will bring to the readers their own river stories. And a feeling that we are all neighbors, and we are all connected by rivers. What we put into rivers will flow away to others. Let it be flower wreaths, rather than waste and pollution.

A work-in-progress of one of the book’s pages: ‘A River is a Connection.’

AN: What Is A River? covers so much ground: from the rituals that humans practice in relation to rivers, to the histories of particular rivers, to the animals that dwell within rivers...how did you set out to map out the book and its trajectory as it flows from one topic to the next?

MV: It is important for me to find a narrative structure for my books where a particular story feels at home.

Creation process of my book started with research. I started gathering river stories of all sorts: facts, various peculiarities, observations, etc. To quickly document them visually, I devised a system of small cards with sketches which helped me note a particular story quickly and see how it could be fitted together with others. In that way, I could play around and see what connections between them can arise, how can they be grouped together.

Monika with her research cards, building the structure of the book. The pink lotus, shown on the card in her hand, later appears in the ‘A River is a Smell’ page.

From the beginning, I imagined “What Is a River?” to be something like an atlas, with a variety of themes detailed in different chapters. Arranging my collection of river stories in different ways all around my studio, I eventually made a list of categories that described what a river – every river – could be: Journey, Home, Refreshment, Name, Meeting place, Riddle, Smell, Memory, Depth, Energy, Reflection, Path, Ocean.

Then, what I was looking for was a possible connection between these chapters. The narrative should flow throughout the book – it was a book about rivers, after all! I knew I had to come up with a reason for myself why all these stories were there, why it mattered to tell them at all. I wanted my book to be more than a compilation of interesting details, and for readers to notice the inner logic in the narrative.

A page from Monika’s sketchbook for What Is A River?

That is how I came up with the two characters, a child and a grandma: they will carry on the narrative in their imaginary expedition to find out what a river is, and will carry the readers’ gaze.

Early sketches for the characters that would anchor the book’s narrative.

The characters of the young girl and her grandmother, who start the book’s journey.

AN: The question at the book’s heart is one that seems deceptively simple at first, but as the book goes on, it is apparent that there are infinite answers. It made me think of the way that children ask so many questions of the adults around them as they attempt to learn about the world, and their own place in it, and the ways in which adults answer them. What are your own feelings about the ways in which we can respect the questions that children ask and encourage their inquisitiveness?

MV: I guess one important thing is to listen attentively when children want to talk with you and not hurry to suggest your definite answer, but rather provide tools that will help children reach their answer. Another thing, I think, is not to dismiss quickly some questions that seem strange or unanswerable.

When I was creating my book, I thought quite a lot about ways questions do come to us, to our heads, what conditions provoke us to question things, to look at the world with wonder.

And I had many questions for myself when I created my book. How to depict conquest, grief, war – alongside joys and wonders? How to be educational, but not didactic? I tried to carefully select my stories so that they did not fall into a single narrative or shy away from difficult questions. You do not need to underestimate children as readers. It is amazing how children sometimes notice so much more than adults. And I think that they notice sincerity, and are not necessarily scared away by things that are not immediately apparent. In the activities that I sometimes do with children, I try to draw their attention to the construction of the story within the book. I try to express a notion that we are all storytellers, that there are infinite ways to tell a story and, quite often, infinite ways to answer a question.

AN: The book quite beautifully combines more fact-based, scientific writing often found in nonfiction, and poetic language. How did you arrive at creating this unique voice for the book?

MV: Lot of facts about rivers are super interesting, in my opinion – but in my book, facts are there not for their own sake or for readers to learn as much as possible. Facts, or nonfiction material, show us what an amazing, abundant place our world is – so many things, both happy and sad, happen all the time. And with language that is more poetic, more abstract, I try to show readers how intricately our world interacts with us, and how many stories hide beneath apparently simple phenomena.

I like to imagine our world as a place where real stories, personal memories, and legends meet and communicate with each other. In my storytelling practice, I look for those miraculous intersections of reality and imagination, and try to communicate them for the readers.

That’s very much the principle I try to follow when I create: nurture mysterious wonderful stories growing from the ground of reality – so that they can put their seeds back, and change our world for the better.

A photo from storytelling time in Vilnius, Lithuania.

AN: What were the sources of your research, not only the history and science, but also the more ‘emotional’ research?

MV: From the start, my research was quite a serendipitous process. I was gathering bits of interesting river stories from all kinds of sources that came into my view: documentaries, encyclopedias, web pages of environmental projects, news articles, old and contemporary photos, descriptions of museums artifacts, ethnographic records, memoirs, various maps. I was also looking for artists and writers that shared similar feelings about rivers that I did, and who were reflecting on how rivers flow through our lives. I discovered works of Robert Hass, Czesław Miłosz, Nick Middleton, Olivia Laing, Maya Lin. I read quite a lot of folk tales about rivers from various cultures. And I also noted my own river memories, associations and thoughts.

A quote from Robert Hass that resonated with Monika.

AN: What Is A River? has been published in many different languages (full list here). As one of the themes of the book is interconnectedness, did this translation of the book into many languages feel, to you, like an extension of this theme?

MV: Yes, in a few ways.

In different editions, illustrations stay the same, but the text undulates like flowing water, and different words flicker on the surface. While preparing the book for publication, I have worked with Swedish, English and Lithuanian translations – these are languages that I know more or less – and it was interesting to compare how different languages catch the message with different words and how that affects the flow of text in the book.

And the traveling of my book, I think, also shows that we humans share so much. I guess that maybe some little details that are dear to me and that I tried to catch and put into my illustrations and words – reflections of stars carried by rivers, ripples of pebbles dancing on water, an afternoon chat with a granny on a riverside, the Earth embroidered by flowing time – found their way into the hearts of readers and publishers and made my story look familiar to them.

AN: The book’s artwork contains many different types of images: some spreads are maps, or diagrams, others are complete scenes as found in many picture books. How did you choose the approach in which you would illustrate each ‘definition’ of a river?

MV: For each spread, I had to divide the content into images and text – as one would do in picture books. I was drawing and writing simultaneously. Sometimes I knew that I definitely had to put on paper a certain image, which I carried in my head, for example, stars flickering on a flowing river; then I would search for words that would complement the image. Sometimes, I first wrote down the words and would then think about which image would fit. All the time, I also thought about the general structure of the whole narrative, its inner dynamics and pace.

Medieval world maps, mappae mundi, also was a source of inspiration. It is fantastic how these maps combine real and fictional realms, how they put together geographical, ethnographical, religious knowledge, how they aim to summarise the whole world view into one entity, how they mix sometimes schematic, sometimes very detailed representation of various places.

AN: There are several recurring images that appear throughout the book: a circular loop, a thread, along with the refrain of ‘a river is…’ For you, what is the importance of the use of repetition? Can you speak a bit about the importance of these repeating visual themes, and how you arrived at them?

MV: I like to use visual metaphors throughout my work. In What Is A River?, you may notice some shapes recurring throughout the story. The circles of the flower wreath, the embroidery loop, the circular river Oceanus around the world; the rectangles in the visual compositions of the spreads, referencing the Grandma’s cloth; and a thread – a physical thread on the grandma’s fabric and in the wreath holding flowers together, and a figurative thread that embroiders stories on the earth and stitches the stories into this book that I am making…

It is not so important that readers notice this repetition. I feel that having some visual principles as a basis for my illustrations helped me put several different stories onto a spread, balance both light and dark stories in one space, and also bring out the poetic side of the stories.

A few early layout ideas.

AN: Can you describe your artistic process when creating the book’s illustrations, and can you show us your workspace?

MV: To get the structure of the book right was the major part of the creative process. I started with storyboards, I redrew them several times, each of them getting shorter, with less pages.

I chose my favorite drawing materials for the final illustrations: colored pencils, water soluble crayons, watercolors, gouache. These materials let me make color gradients and textures, and besides, they give my drawings a feeling of tactility which is important for me – I hope it may invite readers to get drawing themselves. I scanned the drawings that I made and then tidied up in Photoshop.

AN: What are you working on at the moment? What is coming up next?

MV: At the moment I am working on a book for children about the French Impressionist painter Monet. And I am starting another book about nature.

10 ELB Questions (asked in every interview!)

What is your favorite word?

Probably… ačiū. Thank means thank you in Lithuanian. A good looking word with a funny sneezing pronunciation and enormous capacities.

What is your least favorite word?

Well – ‘I don’t know!’ (In Lithuanian, I don’t know is one word, nežinau – but I like it quite a lot.) Or maybe I know – but I would not say it here!

Do you have real life heroes?

My sister. There are many people that look heroic to me – scientists, activists, artists, various people helping others, defying menaces, silently holding our world together – but I don’t know them in their innermost.

What natural gift, other than what you have, would you most like to possess?

Remember all the tender and funny stories my grandparents had told me and put them into conversations in real life to charming effect.

What is your life motto?

Things appear better when put into a poem. Ha ha… Just thought this up.

What is your idea of success?

Being able to allocate time for all the important things in life – being able to create such a balance.

Are rituals part of your creative process?

Not sure. Tidying up my workplace, squeezing out paints, arranging pencils, looking out of my window for a bit – do these count as rituals?

What does procrastination look like for you?

Browsing through online secondhand bookshops or digging through my basket of half-finished sewing projects.

How would you describe your monsters?

Half-broken plastic toys getting into our home in various mysterious ways and looking reproachingly from the dark corners of the house; many-tentacled to-do lists in my phone notes (if you chop down one, three appear in its place); wool moths – quite domestic monsters actually, all of them, and I try to befriend them according to my abilities.

What does earthly happiness look like to you?

Encountering an artwork that my soul missed without knowing it: a book, a painting, a music piece, a handicraft. Sketching outdoors with a good company. Watching my children being friends to each other. Being absorbed in doing what I like. Going to sleep with a calm heart. Friendships, family and grandparents. A good laugh. Seeing our Earth renew, regrow with every spring and bloom.